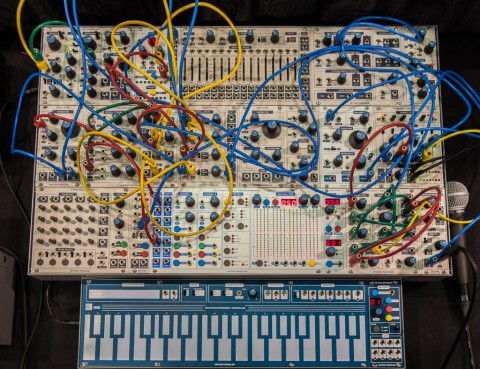

I got to a few more booths today, and wanted to share some more conversations and observations about some of the current directions in modular synthesis. I’ve included links when available if you want more detailed specs on specific modules I mention.

Malekko Heavy Industry

A recently released module Malekko was featuring was the Varigate 4, one of several new timing related modules with a performance bent introduced at NAMM (Make Noise’s Tempi was another). I particularly appreciated how easy it was to set up different timing divisions to play off of one another. Something that’s not immediately apparent is that the sliders tend to be quantized into 8 steps, which is actually a bonus in live performance to assure you hit a desired setting, instead of being continuously variable and increasing the chances you just missed the setting you were aiming for.

(As an aside, I haven’t personally been paying much attention to drum sound modules so far, but the Noise Engineering’s Basimilus Iteritas modules in their rack was really cutting through the noise at NAMM and making a solid impression on my ears.)

The Harvestman

Scott Jaeger of The Harvestman also mentioned that firmware updates were coming for a few existing modules, including the Kermit LFO which I happen to own. The update will improve its performance as an audio oscillator, and also make the tap tempo sync much more solid.

Snazzy FX

The focus, however, was on hi_GAIN: a quad level booster and voltage controlled amplifier. It is designed to overdrive signals in extreme and interesting ways, in response to what Dan Snazelle of Snazzy FX feels has been a desire for more extreme sounds among Eurorack modular users. Each of the four channels uses a different transistor-based circuit design to get different sounds – both to get that vintage guitar fuzz pedal sound, and also to keep the price down (Dan noted that although op amps costs 50 cents each, transistors cost only 5 cents). Each input has voltage controlled gain, meaning you can envelope the amount of overdrive. The CV inputs can be modulated up to audio frequencies to add more character and overtones to the result.

Sputnik Modular

I always admired the design of Sputnik’s 6-Channel Stereo Mixer, but was put off by some users complaining there was audible signal leakage when a channel was muted. Roman admitted there is some leakage (which is hard to avoid in most designs – crank the volume up loud enough, and you’ll often hear something), which he thought was acceptably low when he originally released the module, but based on feedback he has gone through a couple of revisions of the circuit board and will be releasing a much quieter version later this year. In related news, his Spectral Processor (which I am also interested in – I want access to those envelope follower outputs per channel to divide up drum loops and selectively trigger modular sounds) is also due out in a couple of months.

Intellijel

I personally approach modular synthesizers as a large collection of building blocks that I combine to create my sounds, but there are a number of modules such as the Rainmaker that are quite complex as stand alone blocks. Danjel confirmed that this is part of the Cylonix philosophy (also seen in their Shapeshifter meta-oscillator): create really deep modules that the user can spend weeks or months learning the full depths of. This presents an alternate way to configure a personal modular system: a small number of select really deep modules that you spend time mastering to get a wide range of sounds out of, creating a very particular instrument instead of a very generalized one.

Meet the Maker: Modular Synths

It was interesting to hear the panel discuss approaches to designing modules. Dieter Doepfer noted that although it’s important to listen to users, you have to be careful not to design modules that only one user may be asking for (a point echoed by others); on the opposite end, when too many add their voices to the mix, a module design may become so unwieldy that it has to be abandoned. William Mathewson is a tinkerer that likes to grow circuit ideas into modules for his own WMD line, whereas the joint WMD/SSF modules had their front panels designed before they started on the circuits. Tony Rolando likes to start with a written “essay” of what a module should be before starting actual circuit design; Dan Green starts by answering the question “what’s missing?” when he creates music. Gene Stopp also made the interesting observation that the Model 15, 35, and 55 modular systems that Moog re-issued are considered to be continuations of the original systems rather than recreations or clones – but in the process of making them, they learned just what gave them their unique sound which can be applied to future products.

After two full days, I feel like I’ve seen fewer than half of the modular manufacturers at the NAMM show this year. Fortunately, my remaining prey are all clustered in the same section of Hall C, so that’s where I’ll be for a few hours on Saturday. I’m on the road immediately afterward, so it may take awhile to file a final report, but it’ll give me more time to ponder what overall trends seem to be flowing through the modular market today.

Any thoughts on the pricing of cases? It seems to me that case pricing has gotten a little out of hand. People seem to have settled on a price per HP that the market is willing to pay and almost every case sits in a fairly narrow range, almost regardless of construction type, features, portability, etc. I find it very frustrating that, short of building something myself, I will have to pay what seems to be an obscene amount for a box with some rails and a power supply, and if I then go to a totally mass produced extruded aluminum case with no tolex, cheaper latches, and far lower manufacturing costs, I still pay pretty much exactly the same money, if not more. It seems a little like cases and patch cables have these guaranteed prices that manufacturers expect us all to be willing to pay, no matter the quality of the product. It’s a little odd.

Case in point – Doepfer “Low Cost” Base and “Low Cost” Case have 5 rows of 84HP for 420 HP in total. For $490 and $460 total. That’s 2.26/HP. Doepfer’s high end monster cases cost a whopping $2.48/HP. “Low Cost” seems a total misnomer here. Intellijel’s new extruded aluminum case (the lid of which is going to survive about 5 minutes before it is a misshapen sheet of bent aluminum unless you are VERY careful with it), is going to cost $500-$600 for 7u of 84HP, so that’s $3.00/HP, for the cheapest possible construction. There were 2 or 3 other extruded aluminum cases in the same price ballpark. How come no one is able to make a box with some rails for $20-$30, plus a power supply? Even at low, modular synth volumes, I have a very hard time believing that we all aren’t being taken for a ride on these cases.

I too am constantly surprised at the cost of cases, until I think about exactly what’s involved.

Remember that all of these manufacturers are pretty low volume, so there’s no option to have them built really cheap in China and sent back on a container ship. So go price out the cost of all the hardware involved (as in, all – every screw, bit of glue, etc.) – they’re not going to pay much less than you and me, as there’s little to no quantity break for the numbers we’re talking – and then add in the cost of your labor (or an employee’s labor) to build it and package it up. Add a bit on top to amortize the design time you spent, plus a slice for the tools you had to buy to make it. Don’t forget the cost of the box it goes into for shipping, and the time spent moving things around, from ordering parts, to moving things around from raw materials to partially finished cases to putting a complete unit in storage somewhere, taking it out of storage (did you add in rent for the larger facility to store these?), and shipping it off to a dealer. Add in the profit margin you’d like to make for your efforts. (If you have them built out of house for you, then the other place has to make a profit too, although hopefully they have some savings in other efficiencies.) Then add in at least 60% (or to be safe, double it) for the dealer’s margin – you can’t charge less than dealer for direct sales, or the dealer will drop you. Oh, and shipping to the dealer – from Germany, in Doepfer’s cases. Add in more margin to cover breakage, getting stuck with left over inventory, for the demo units you don’t make any money back on, etc.

The price goes up frighteningly quickly from raw materials to a finished product that you’re not going to lose money on. Same goes for the power supplies that go into the cases. So no, I don’t think there’s price fixing, or an attempt to screw anyone over; it’s just economic reality of building labor-intensive stuff in small quantities once you become aware of what a manufacturer actually has to go through. Or, you can go buy those laser-cut “stackable” cases that you assemble yourself for a pretty reasonable price because they leave out all these assembly and storage steps.

BTW, the thick extruded aluminum going into some of these cases is not like a thin rain gutter or the such – it’s very tough. Think aluminum softball bats – they hardly crumble on first hit.

Nice article. Keep ’em coming.

Nice article, well written and yes, please do keep them coming!