I spent a lot of time in September on two projects: the 50th anniversary of the ARP 2500 modular synthesizer, and extending the “wave splicing” idea appearing on some oscillators to encompass a general way to create more interesting audio and modulation waveforms. That’s reflected in the videos and articles I’ve created over the past few weeks:

- featured article: A simple tweak to the typical synthesizer patch that has been producing more interesting, animated sounds.

- new videos & posts: A tube-based vintage effects module, vignettes on the ARP 2500, and more.

- course updates: More opportunities to ask questions & share.

- Patreon updates: More exclusive posts to flesh out my recent videos, plus a set of advanced patch ideas inspired by the TB-303.

- upcoming events: SoundMit 2020: Virtual Edition.

- one more thing: The ARP 2500’s 50th Anniversary, and remembering synthesizer history in general.

Using Crossfades to Create More Complex Waveforms

I’ve been playing around with some simple extensions to the typical synthesizer voice patch that has been producing some interesting results:

- Replace the typical oscillator or waveform mixer with a crossfader.

- Then try using all sorts of different modulation sources for the crossfade, from simple LFOs and envelopes to audio-rate crossfades using a third waveform or oscillator.

- Then, extend the idea to LFOs and other modulation sources, as well.

The video above is a demo I gave to a New Mexico Control Voltage modular meetup featuring some of my VCO crossfading experiments. Click here for an article on the Learning Modular web site that explains these patch ideas in much more detail. Below is a brief version of that article.

Starting Simple

This technique uses the oscillators, VCAs, LFOs, etc. you already have, but you may need to add one more module: a crossfader. In general, the analog crossfaders I’ve tried have no problem being used at audio rates, while some digital ones can start to act odd at those rates.

To start, patch two VCOs – or two waveforms from the same VCO – into the crossfader’s two inputs, A and B. Use the manual crossfade position control available on most crossfader modules to set the initial mix between the two sources. Then patch the output of the crossfader into the rest of your normal voice chain, such as to a VCF or a wave folder.

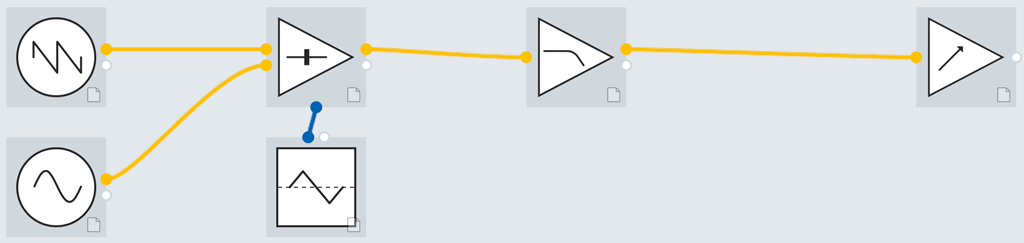

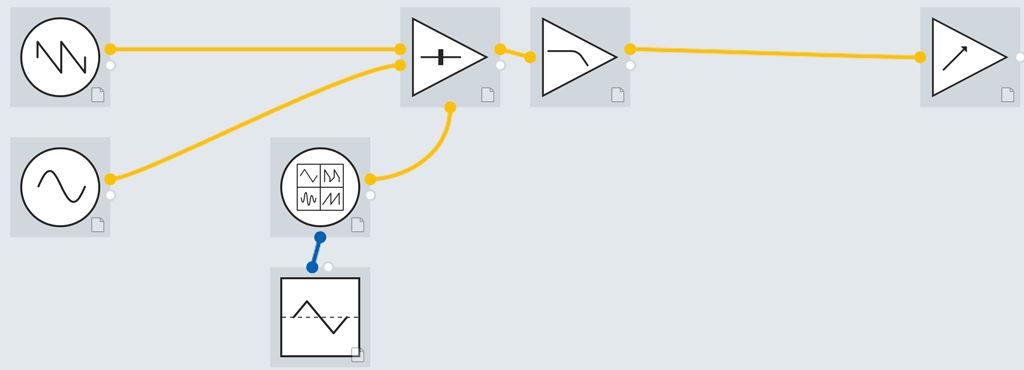

Now animate that mix. Center the crossfader’s initial position (50% each of A and B), and patch the LFO into the CV input for the fade, playing with the modulation depth to set how wide of a timbral sweep you’ll hear:

(diagrams from the Patch & Tweak online patch editor)

Then try other modulation sources, such as an envelope generator (patch tweaking suggestions are in the main article), a smooth random voltage generator, or a sample & hold that might be triggered at the start of every note. You can also try performance controls such as a mod wheel, velocity, aftertouch, or an extra channel from your sequencer to control the crossfade.

Audio Rate Crossfading

This simple starting point will add some relatively gentle timbral movement. But the real fun begins when you modulate the crossfade at audio rates, using another waveform output or an additional VCO.

In this case, you would patch separate source waveforms into the A and B inputs, as well as into the crossfade control voltage input. The output will contain harmonics from at least all three of those sources, and probably more.

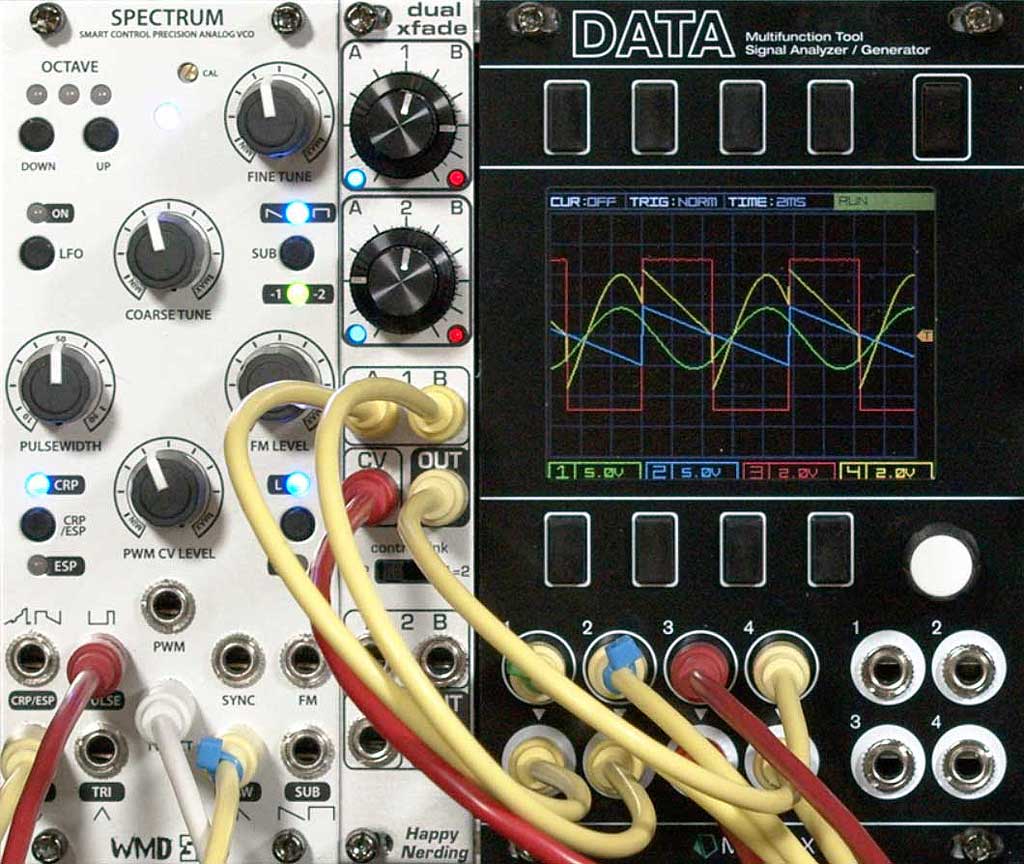

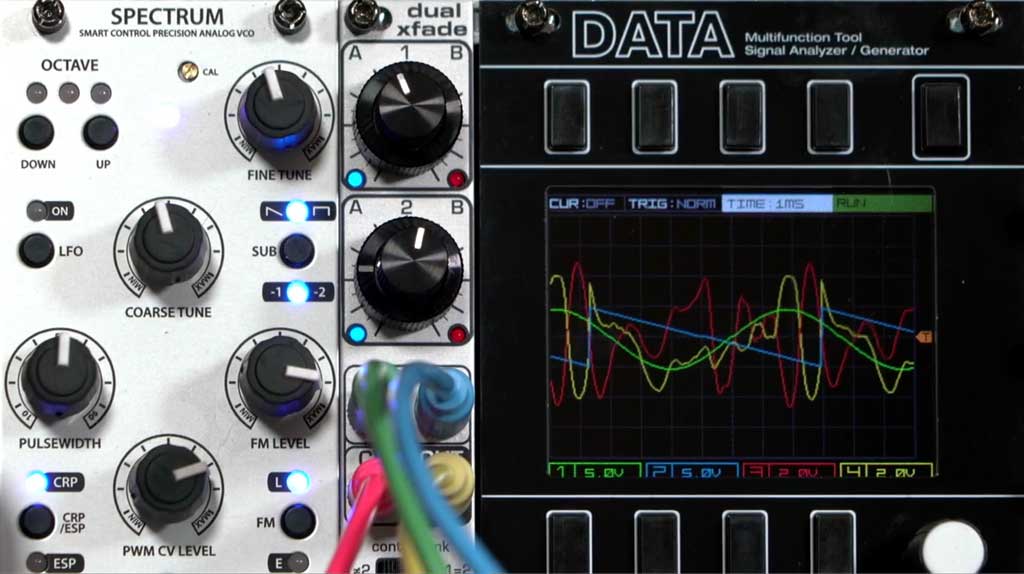

If the crossfade control waveform also happens to have a sudden jump in level – such as a sawtooth or pulse wave – this will most likely cause a sudden jump in level as you switch from input A to B (or back), as their individual waveforms will probably not line up at this switch point:

Above: green = waveform A; blue = waveform B, red = crossfade waveform, yellow = output

If all three waveforms come from the same oscillator (as in the image above) – or from different oscillators that have been synchronized – the output will be a static, unchanging timbre. Things get far more interesting if you can introduce changes in any of the component waveforms.

For example, say you used a pulse wave for the crossfade CV, as shown above. You could use an LFO, envelope generator, or other modulator to vary the width of this pulse:

Modulating the width of the pulse not only animates the harmonic mix, but also moves the sudden discontinuous jump between the A and B source waveforms, resulting in a sound somewhere between pulse width modulation and hard sync. This is the idea behind “wave splicing” oscillators such as the Dove Audio WTF (Window Transform Function) Module, the Future Sounds Systems OSC2 Recombination Engine, and the MOK Waverazor.

Life gets even more interesting if you change the tuning of the three component waveforms. Just using three separate oscillators tuned to the same pitch will probably exhibit subtle phasing between them, resulting in the harmonics fading in and out without the need for additional modulation. Tuning the components to different octaves introduces even more interest and a wider range of harmonics.

To create a smoother composite sound with fewer high harmonics but still a lot of rich movement in the middle harmonics, use a waveform other than a pulse to perform the crossfade. It’s even better if you can modulate the shape of this crossfade wave, just as you could the pulse width.

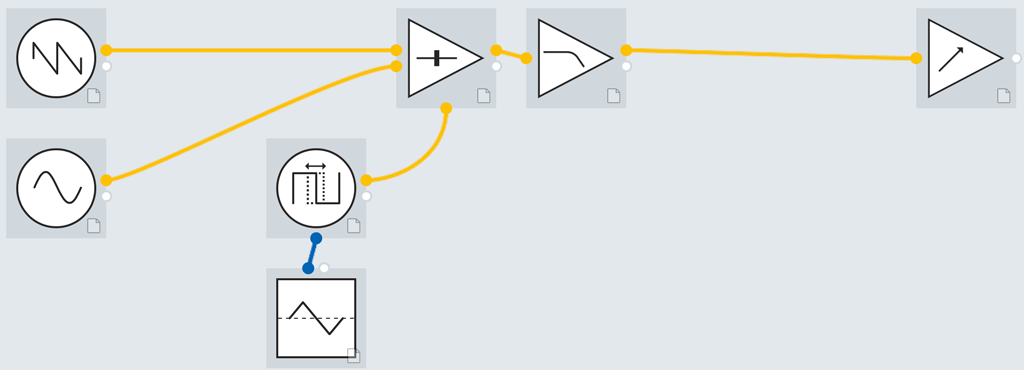

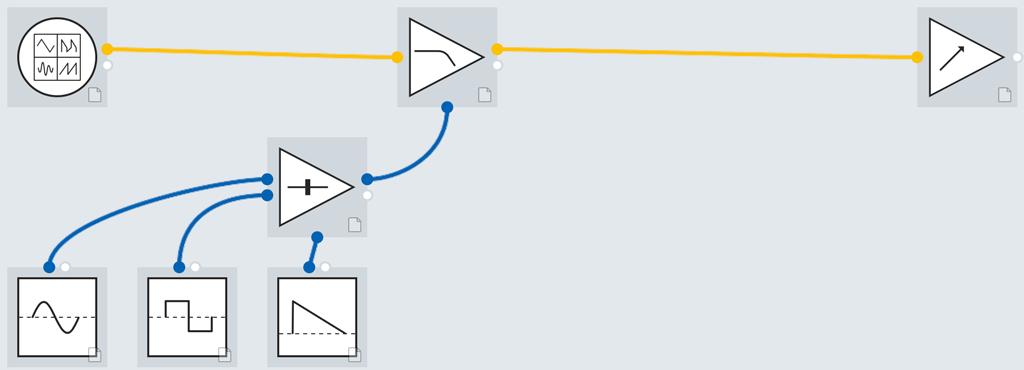

The last few minutes of the video above demonstrates scanning between waveshapes in a digital wavetable oscillator to drive the crossfade; the effect can be quite complex, including vocal-ish sounds. That patch and resulting waveforms is shown below:

Improving LFO Waveforms

Happy with how this crossfading technique has breathed new life into my oscillator waveforms, I have started to experiment with using it for LFO waveforms as well. A crossfader and a few LFO waveshapes – or even better, multiple LFOs with independent rates – can create their own exotic, morphing waveshapes. Here is a simple patch using an Attack/Decay envelope generator to fade from one LFO to another during each note:

A popular LFO module is the DivKid/Instruō øchd, which includes eight triangles waves that each run at different yet connected rates. This is an excellent module to pair with a crossfader.

The output of this can then be used to modulate anything you would normally drive with an LFO, such as pulse width, filter cutoff, a phase shifter or flanger, or even the crossfader for your VCO waveshapes.

Overall, his technique provides a relatively easy way to get those results, just by adding a crossfader to your existing modules. Again, refer to the longer article on the Learning Modular web site for more details, including additional videos and background information.

New Videos & Blog Posts

I created a set of five short videos discussing various features of the vintage ARP 2500 modular synth; those will be discussed in more detail in the One More Thing section at the end of this newsletter. I also released the following videos:

I reviewed the Erica Synths Fusion Delay/Flanger/Ensemble module. This module marries together an analog BBD delay line, tube-based saturation, and a low pass filter as well as a simple trick to create a fake stereo field from a monophonic source.

I also created two videos based on my “waveform crossfading” idea discussed in the main article above. In addition to the New Mexico Control Voltage modular meetup demo featured there, I also created the video above to explain “wave splicing” and my extension of using crossfading rather than a hard switch.

And, over on the Synth & Software web site, I have a review of the MOK Waverazor Dual Oscillator (which is one of the wave splicing VCOs that sent me down the path of exploring crossfading).

Modular Courses Updates

I added the Erica Fusion Delay/Flanger/Ensemble video to the Eurorack Expansion: Extended course, in the Effects section.

As some of you have noticed, I also added the ability to comment on each “lesson” inside of each course. My next step during October is to make sure everyone registered in a course has access to the overall community for their courses, in case you have questions or want to share ideas that go beyond an individual lesson.

Patreon Updates

The most significant Patreon-exclusive post I created last month (for +5v and above subscribers) was a long piece dissecting two of the sections of the Roland TB-303 that made it unique – its filter, and its Accent function (neither may be what you thought) – and showing how to recreate them generically in your own modular patches.

+5v and above subscribers also received more detail on the Erica Fusion Delay/Flanger/Vintage Ensemble, plus an exclusive bonus video on using it in feedback to create its own soundscapes.

All subscribers also got to view a detailed post on the Wave Splicing idea, plus a couple of comments on my Wave Crossfading demo.

They also received companion posts for the five ARP 2500 50th Anniversary videos I created, including:

- Patching with Switch Matricies

- Module 1047 Multimode Filter/Resonator

- Module 1027 Clocked Sequential Control

- Module 1050 Mix Sequencer

- Analog Computers and Modular Synthesizers

Those posts are more detailed than others that have appeared publicly – a perk of being a Learning Modular Patron.

And, as a follow-up to that last post on the 2500, I also shared last week some more resources on using analog computers and test equipment for electronic music.

Upcoming Events

The Italian synth & pedal show SoundMit is having its 10th anniversary edition online – and it will also be free to all virtual attendees. I will be giving a session that further expands on my wave crossfading idea above, with a live question & answer period. The show will be webcast on SoundMit’s YouTube channel, November 14 & 15.

One More Thing…

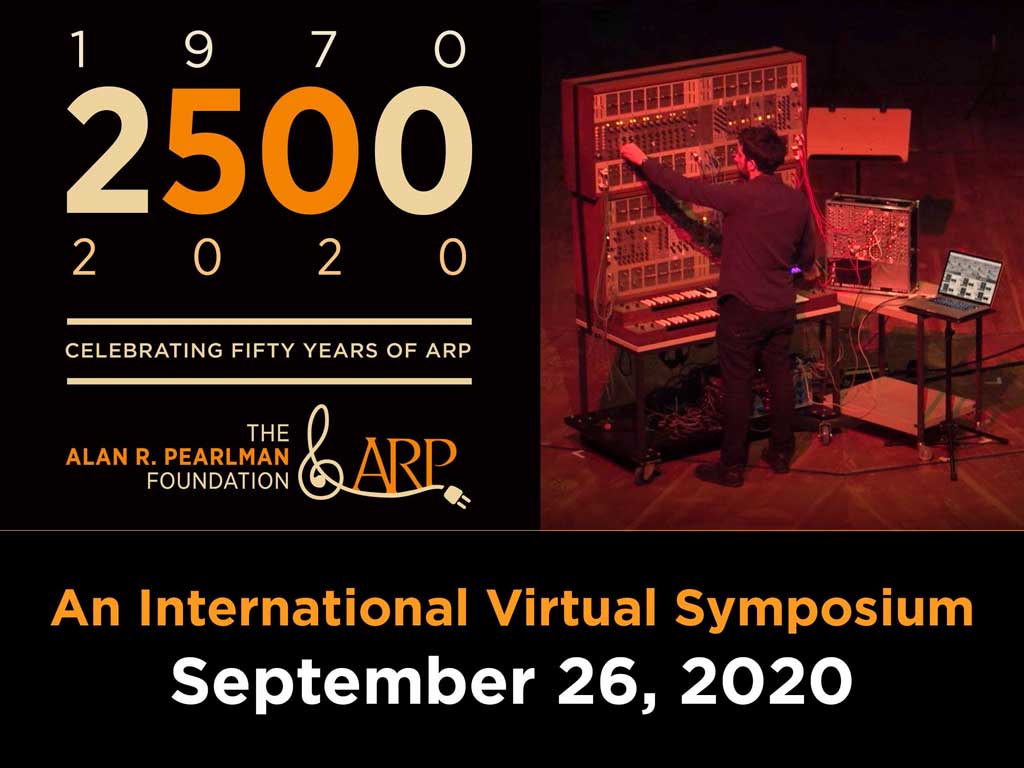

The ARP 2500 modular synthesizer – the one seen near the end of the movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind, communicating with the alien spacecraft (that’s ARP employee and old friend Phil Dodds at the controls – we miss him) – celebrated its 50th Anniversary this year. To mark the occasion, the Alan R Pearlman Foundation – founded by Alan’s daughter Dina – held an online “synthposium” in its honor, featuring some of the original engineers as well as numerous musicians and educators familiar with the 2500, including Jean-Michel Jarre.

I created a series of short videos + accompanying articles about the 2500, plus co-moderated the Education panel with Dina. The synthposium itself is being edited by Dina (to remove the various glitches and insert the videos that didn’t play correctly); those movies are being uploaded to the Foundation’s YouTube channel – two sessions are up now with more to follow.

I am a supporter of the Alan R Pearlman Foundation, as well as the Bob Moog Foundation. I think it’s important to preserve information about the early days of both the machines and the music of our favorite “industry.”

Why? I recently watched an online seminar of an innovative new software synth, and its creator started by giving an overview of other synthesis methods from the past. There was a lot of good information in there, but also some incorrect information – including a belief that popular music didn’t start using samplers and synths until the 2000s! A lot of people in the chat room were thanking him for sharing this sometimes-erroneous information, as they had not heard it before.

That kind of alarmed me. And now that many of those from synthesizers’ first generation are no longer with us, we run the risk of forgetting where we came from. So let’s help keep those memories alive.

Apologies for this newsletter coming out a little later than normal; I spent a week hiking around the White Mountains of Arizona, learning how to use my new Shure MV88 mid-side microphone with my iPhone, capturing natural soundscapes to integrate with my music. But now I’m back in the studio, playing with music and learning more modules. I’ll be sure to share the results with you in the upcoming weeks and months.

best regards –

Chris